The environment is becoming an increasingly important topic for airlines. Not only are we seeing airlines take delivery of more fuel-efficient aircraft and offset emissions, but we’re also seeing the development of all new aircraft technology.

In September 2020, Airbus revealed zero-emission commercial aircraft concepts. Now Brazilian aircraft manufacturer Embraer has unveiled four new aircraft concepts using renewable energy propulsion technologies, which could enter service in 2030-2040… maybe.

In this post:

Embraer’s Energia aircraft lineup

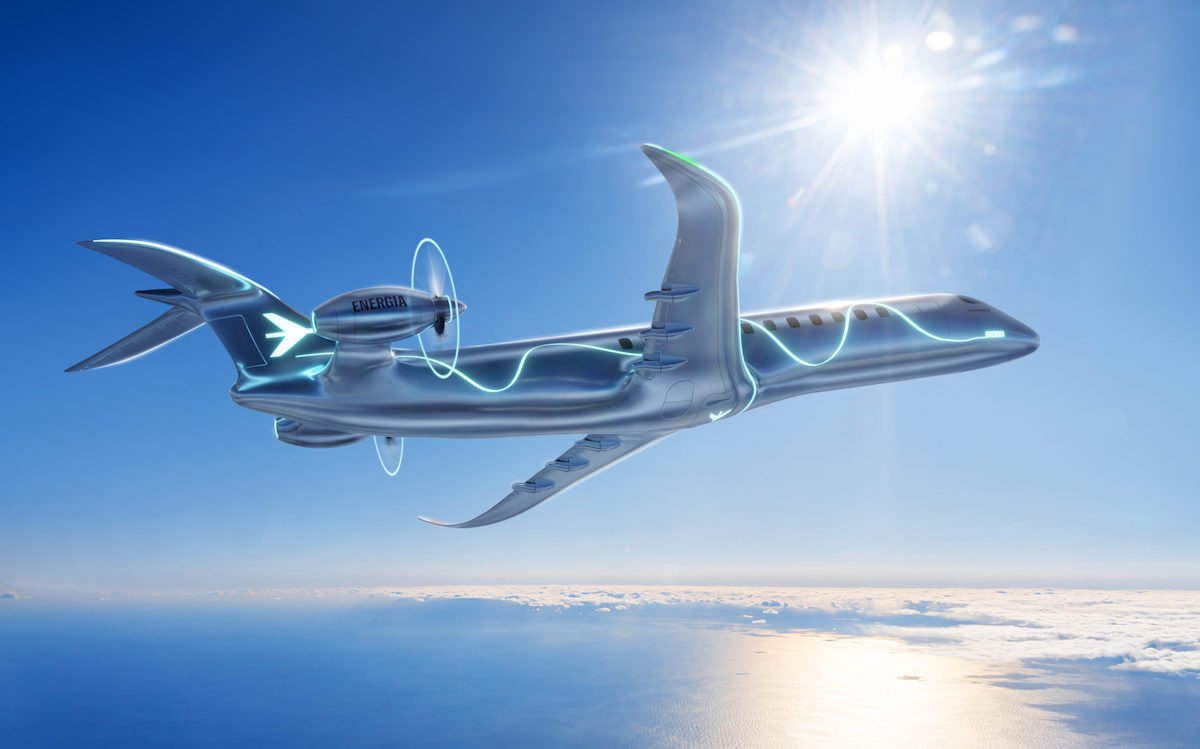

Embraer has today announced a family of concept aircraft that are being explored to help the industry achieve the goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. There are a total of four planes, known as the Energia family, which could feature anywhere from nine to 50 seats, and which could be flying between 2030 and 2040. Each aircraft is currently being evaluated for its technical and commercial viability (in other words, it could very well be that these planes never enter service… only time will tell).

Embraer has partnered with an international consortium of engineering universities, aeronautical research institutes, and small and medium-sized enterprises to better understand energy harvesting, storage, thermal management, and their applications for sustainable aircraft propulsion.

The four concept aircraft are varying sizes, and incorporate different propulsion technologies, including electric, hydrogen fuel cell, dual fuel gas turbine, and hybrid-electric.

Here’s how Luis Carlos Affonso, Embraer’s SVP of Engineering, Technology, and Corporate Strategy, describes this latest move:

“We see our role as a developer of novel technologies to help the industry achieve its sustainability targets. There’s no easy or single solution in getting to net zero. New technologies and their supporting infrastructure will come online over time. We’re working right now to refine the first airplane concepts, the ones that can start reducing emissions sooner rather than later. Small aircraft are ideal on which to test and prove new propulsion technologies so that they can be scaled up to larger aircraft. That’s why our Energia family is such an important platform.”

Let’s go over the basics of the four concepts, roughly from smallest to largest.

Embraer Energia Hybrid

The Embraer Energia Hybrid:

- Would be a hybrid-electric propulsion aircraft

- Would reduce CO2 emissions by up to 90%

- Would have nine seats

- Would have rear-mounted engines

- The technology could be ready by 2030

Embraer Energia Electric

The Embraer Energia Electric:

- Would feature full electric propulsion

- Would have zero CO2 emissions

- Would have nine seats

- Would have aft contra-rotating propellers

- The technology could be ready by 2035

Embraer Energia H2 Fuel Cell

The Embraer Energia H2 Fuel Cell:

- Would feature hydrogen electric propulsion

- Would have zero CO2 emissions

- Would have 19 seats

- Would have rear-mounted electric engines

- The technology could be ready by 2035

Embraer Energia H2 Gas Turbine

The Embraer Energia H2 Gas Turbine:

- Would feature hydrogen or SAF/JetA turbine propulsion

- Would reduce CO2 emissions by up to 100%

- Would have 35-50 seats

- Would have rear-mounted engines

- The technology could be ready by 2040

Embraer’s 2030 sustainable aviation fuel target

Separate from the Energia aircraft family concept, Embraer is more immediately working on reducing emissions by making all E-jets compatible with sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), which mixes sugarcane and camelina plant-derived fuel and fossil fuel. The company is hoping to have all Embraer aircraft be SAF-compatible by 2030.

That’s only one of the initiatives that Embraer is working on to reduce emissions. In August 2020, Embraer also flew its electric demonstrator, a single-engine EMB-203 Ipanema, 100% powered by electricity. A hydrogen fuel cell demonstrator is planned for 2025, and Embraer’s eVTOL (fully electric, zero-emissions vertical takeoff and landing vehicle) is being developed to enter service in 2026.

Bottom line

Embraer has revealed its new Energia aircraft concept, which is a lineup of four sustainable aircraft that could seat anywhere from nine to 50 people. These concepts are in the very early stages, and it’s anyone’s guess if these specific planes ever fly.

In general it’s great to see aircraft manufacturers investing resources into exploring this new technology because eventually, it will be absolutely vital. There are obviously lots of logistical challenges (aircraft pricing, electric charging, getting this type of technology on larger aircraft, etc.), but I imagine over time that’s nothing that can’t be overcome.

Along similar lines, I think the Wright brothers would have thought there would be logistical challenges to a double-decker plane with a bar and shower, but hey, here we are — that plane is about to be outdated technology! 😉

What do you make of Embraer’s new sustainable aircraft concepts?

It's good that the aviation industry is taking action on the zero emission requirements and demands, but they should stay realistic. Most major aircraft producers, including Airbus, have given their creative department a blast with drawing up this kind of concepts. Lots of cool ideas, but most of them not realistic. In other words: these planes most likely won't ever fly. I'll explain why.

Looking at the proposed planes, we can see two initial...

It's good that the aviation industry is taking action on the zero emission requirements and demands, but they should stay realistic. Most major aircraft producers, including Airbus, have given their creative department a blast with drawing up this kind of concepts. Lots of cool ideas, but most of them not realistic. In other words: these planes most likely won't ever fly. I'll explain why.

Looking at the proposed planes, we can see two initial other issues: short haul and low capacity. Given how business travel has been radically changed due to the pandemic, how governments are making demands about reducing the amount of (ultra) short flights and investing in alternatives like high speed railways (Lufthansa, KLM and AirFrance even include train tickets as part of their itineraries already) or even hyperloop and other futuristic development, you'll end up with niche markets like Norway and Northern Canada, where even building roads simply isn't a viable alternative. But then, 9 seaters aren't a viable commercial investment. Even in Finnmark, Widerøe uses 39 seaters now, and with good reason. Widerøe would be interested in more efficient aircraft and significantly reducing their footprint, they already said so, but they have alternative projects ongoing now.

First, let's draw the requirements for fuel: the whole fuel train should be relatively lightweight, it should be portable and it should have a high enough caloric value per kilo and per liter to make it usable.

Battery technology has largely been unchanged in the last 100+ years. Sure, the capacity and efficiency have been severely improved, but the principles and technology remain largely the same. The CEO of Austrian published a statement just a few years ago in which he said that converting a 767 to fully electric for a trip from Vienna to New York would require about 3000 tons of batteries. Which is about 20 times the current MTOW.

If we look at the fuel cell and other hydrogen based solutions, then we're still having a few issues to solve. First, there will be a huge amount of hydrogen required to fly a plane. Not only does that cost a good amount of money to make, it also comes with some other issues. Like safety. Capturing hydrogen in tanks isn't as straightforward as it seems, due to hydrogen being the smallest element and due to the temperatures required to store it. We've seen a few cases in which a hydrogen fuel station nearly spontaneously blew up, for example. You can't have that mid air. We need to fix that first and it doesn't seem that a viable, lasting solution is nearby. The other thing is efficiency. There are over a dozen different fuel cell technologies now and the most promising has an efficiency rate of about 60%.

They might look into the use of liquified natural gas for the time being. It's much cleaner than kerosine and sort of fulfills the other requirements for fuel. It should also be available on a short notice. That may give some additional time to further develop and solve issues on other fuel types.

I've seen a lot of developments here, from a different type of turboprop to blended wing aircraft to aircraft with solar panels built in (yeah, that will add some weight and plese don't fly by night), but I don't see The Solution yet. We need more time for that, so then gradual change might be the most viable way forward. Not one big leap to perfection, but several smaller steps.

Low passenger carrying, short haul, electrically driven aircraft may be becoming more viable in the next 10-20 years with advancements in higher density batteries. To date, the only major commercial aircraft to take a leap in this direction is the B787 with it's electrically powered surfaces but the propulsion remains a petroleum-based turbofan. Simply, batteries are heavy, have low energy densities and contribute to a high weight-to-thrust ratio.

The hydrogen economy has been tried and...

Low passenger carrying, short haul, electrically driven aircraft may be becoming more viable in the next 10-20 years with advancements in higher density batteries. To date, the only major commercial aircraft to take a leap in this direction is the B787 with it's electrically powered surfaces but the propulsion remains a petroleum-based turbofan. Simply, batteries are heavy, have low energy densities and contribute to a high weight-to-thrust ratio.

The hydrogen economy has been tried and tested in various scales over the years. However, I see little progress in the major use of hydrogen as an alternative to petroleum even in the future. The low density of hydrogen requires high cryogenic compression to store any substantial value of energy. While hydrogen has a high specific energy density, it's volumetric energy density remains low without substantial compression. There are inherent problems with flying around holding large tanks of compressed combustible substance with a low-ignition-limit like hydrogen. Even if we overcome the practical problems with storage and calorific value, cultivation of hydrogen consumes excessive energy, either through hydrolysis or through pyrolysis and/or gasification. The latter two also releasing large quantities of GHGs in the process and all requiring a primary energy source. Due to all this, I consider natural gas is a more viable alternative. It is cleaner (than jet kerosene), more efficient as a fuel and easily adaptable to the existing gas turbines. Nat gas can be extracted as it is done today or synthesized through gasification or biochemical pathways.

So while I am all for the advancement of science and genuinely wish Embraer the best, I would place my money on renewable (maybe bio) fuels and more efficient aircraft engine concepts, including the return to turboprops, because they are extremely efficient and latest designs are quiet. Ultimately, the underlying issue at hand is not the energy that we use in the aircraft, but how we produce that energy to begin with. Electricity, hydrogen, jet kerosene, natural gas can all be created through carbon neutral or carbon intensive methods - the cost remains the prohibitive factor for the former.

Clearly a topic I very much am invested in.

Fuel efficiency is improves with more passengers so these tiny tots will not be very cost efficient nor will they be a lot of fun to fly. Maybe for 100 km to 500 km?

Range? Not much chance of TP or TA.

Lets go back to derigibles. They make a lot more sense. And the gas in the bag can be used for fuel.

Sounds more like this.

Let's throw in 4 concepts, let's see which one will get Government subsidy, or some investment money. All are there just to keep activists from making noise.

If any of these things are really the main focus of the market, we would be seeing a lot more turboprops flying and fewer regional jets.

@Eskimo - you might be surprised by the level of Embraer's commitment to this. Arjan Meijer, their new CEO, has been a staunch proponent of the next-generation turboprop (the so-called "E3 Turboprop") since before he was appointed to the role and he has pretty much bet the company's future on that being a success.

Thanks for the update, very interesting and fast moving area.

While these are great concepts for the future, I wouldn't be surprised to see Embraer leapfrog some parts of this technology into the development of their new E3 turboprop that is already underway.