Miles Aren’t Free: How To Value Your Redemptions

Miles Aren’t Free: How To Value What You Earn

Miles Aren’t Free: Establishing An Overall Value

There has been a lot of buzz lately about the idea of free travel. The reality is that miles have a value just like any other currency you hold. You can choose to redeem them for a first class ticket, or for an economy ticket, or for a toaster. And in each case, you are getting different redemption values. It’s not to say that any of those redemptions are wrong, per se, but you should at least be aware of how much value you are getting each time you redeem miles. You can use that information to set an upper bound on your personal mileage valuation. I explained that concept in Part 1 of this series, How To Value Your Redemptions.

On the other side of the coin is mileage earning. Nowadays it’s possible to earn miles in a lot of different ways, from credit card sign-up bonuses, to shopping portals, to mileage running, to plain old actual flying. Even though it may seem like it, most of these miles aren’t really free. They either took some effort to obtain or there was a choice to earn cash instead, so there was a trade-off. The fact that you chose to earn miles instead of cash — or not at all — says a lot about how you value your miles. Just by undertaking a given activity, you are implicitly stating that you value your miles at more than it costs you to obtain them. This was the focus of Part 2, How To Value What you Earn.

In this final post of the series, I’m going to combine the redemption theory with the earning side to help you think about your overall mileage valuation. The idea being that if you simultaneously understand both the cost of the miles that you earn and the value that you get when we redeem them, you will make better decisions on both ends.

Earning and Redeeming

Prior to now, I’ve talked about redeeming and earning separately in order to develop the framework. Now let’s put them together.

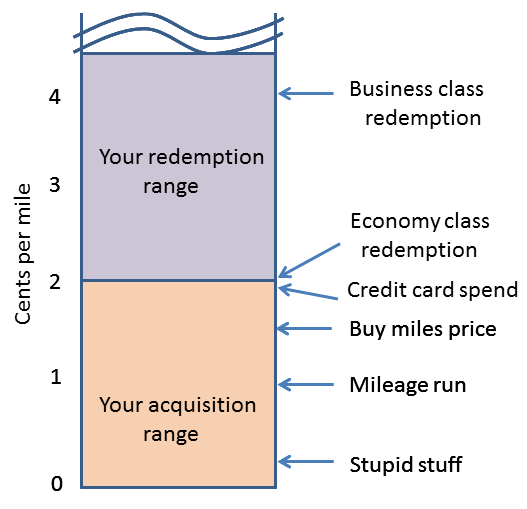

The thing that should jump out at you from this figure is that the redemption range and the acquisition range actually abut each other. This is both interesting and potentially problematic.

You might recall that the lower bound of the redemption range was determined by the lowest rate at which you were willing to redeem miles. In the example, that turned out to be 2 cents per mile (CPM) based on the economy ticket. The upper bound on the acquisition range was then the highest price you were willing to pay for a mile. That was also 2 cents since you were using a mileage earning credit card instead of a cashback card.

Well, if you’re willing to redeem miles as low as 2 cents, and you’re willing to buy miles at 2 cents, then you must therefore value your miles at exactly 2 cents. There’s no middle ground. There’s no wiggle room. There’s no range of possibilities. Based on your hypothetical behavior that we assumed for this example, your personal mileage valuation is 2 cents. End of story.

For what it’s worth, I know you won’t believe me, but I didn’t actually plan it to turn out this way — I kind of wanted there to be a gap between the lower bound and the upper bound of your mileage valuation. But I guess that’s what happens when you publish the first chapter of a book before you write the last chapter. (On the other hand, now I know how J.J. Abrams felt when he got to the last season of Lost and was like how the hell am I going to explain this damn smoke monster, the fact that my island travels through time, and everything else I created back when I didn’t think anybody would actually watch this show.)

What It Means

I may not have intended it to turn out this way, but honestly it’s not that far-fetched for a lot of people. And for that matter, it could be worse — like what if the example showed that you were buying miles at a rate higher than you were redeeming them at? (Sadly, I’m sure that happens too.) So let’s just deal with it.

Buying and selling miles at the same rate doesn’t make a lot of sense, plain and simple. There’s really nothing to be gained. It’s like buying a car from Peter in the morning, and then turning around and selling it to Paul in the afternoon for the same price. Except that you are the one that’s getting robbed. Or at least not compensated for taking risk. The equivalent in the mileage world is that you bought Delta miles yesterday for 2 cents with the intention to use them today at 2 cents, but in the interim Delta destroyed their award chart. Like that would ever happen…

This is not to say that there’s anything wrong with either buying miles or redeeming them at 2 cents each. The issue is that you shouldn’t be doing both.

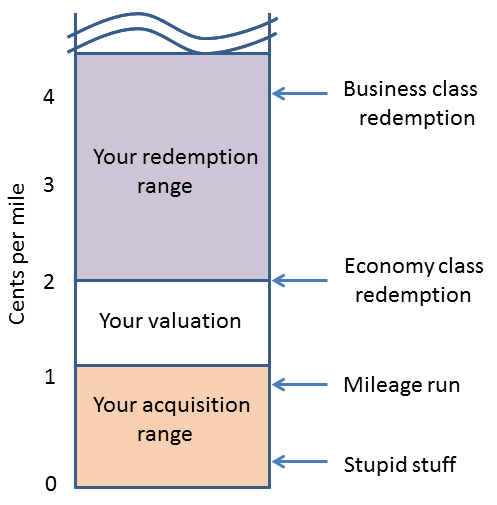

Mind The Gap

Simply put, you should want to have a gap between the rate at which you earn and redeem. That means that if you are ready, willing, and able to pay for premium cabin travel, then you may well value miles at well above 2 cents each. That’s great. But that means that you should not be using miles for lower value redemptions. You can’t have it both ways.

Most folks don’t buy revenue business or first class tickets though. And honestly, most of the world doesn’t even redeem for premium cabin award tickets. The domestic economy ticket is the most common redemption out there, so clearly a lot of people go for it. And there’s nothing wrong with that either.

But if you’re willing to accept a 2 cent or less redemption, you should want to be earning miles at much less than that. That means most of the purchase mile opportunities are out the window, and you should even think long and hard about whether you should be putting regular everyday spend on a mileage earning credit card after you’ve met the minimum spend.

In other words, no matter whether you like to redeem for high CPM awards or low, aim for a gap between the rate at which you buy and sell, almost like a bid – ask spread.

Bottom Line

Valuing your miles is a very subjective process. Trust me, it takes a long time to internalize your own personal value of miles. When I was getting started, I mostly relied on guys like Ben to tell me what they were worth. It was only after years of playing the game that I started to get a feel for how much effort I would expend earning miles, and when I would prefer to pay cash as opposed to redeeming them. It definitely didn’t happen overnight.

That said, if you’re new to miles and points, you can certainly start to think about how you earn miles now, and how you might spend them going forward. The most important rule is that you want to get more value out of redeeming them you paid to acquire them. I know, that seems utterly obvious, but you might be surprised at how many people violate that premise without even realizing it. Just as with investing, the idea is to have a plan and stick with it.

Oh, and don’t beat yourself up if you slip up once in a while. Humans aren’t robots– even when the numbers say we should do one thing, we sometimes do another. Behavioral finance has shown that when faced in pressure situations — say when trying to book travel due to a family emergency in another state — people tend to make irrational decisions. Even though you may know that your miles are worth almost 2 cents each to you, it is still tempting to redeem an insane lot of them to avoid the last minute ticket. But knowing that we are prone to such behavior can help us recognize it, and stick to our game plan.

Conclusion

Establishing the value of a mile is a challenging and subjective process. Everybody has different opportunities to earn miles and difference preferences for redeeming them and that will influence their personal valuations. Those valuations may also vary over time as earning and redemption patterns change. Your valuation may also change as your pile of miles grows larger and larger — the more you have, the lower the rate that you may be willing to accept in terms of redeeming them, and the lower the cost you might demand in order to buy them.

At any rate, I hope that this framework helps you to start thinking about how you personally value your miles. Although it is difficult to come up with an absolute number, establishing bounds on both the upper and lower end of your valuation range can help you both decide when and how to acquire miles and when redemptions make sense for you. And remember, miles are a form of currency — don’t think of them as free.

Great, another post about how miles aren't free - how many more of these are you going to post. We're not idiots you know

The MyPoints 750 point bonus's "sweet spot" is to keep miles from expiring. For example, my partner has about 50,000 UA miles in her account, but all her recent UA flights have been on awards booked from my account. So she hasn't had real activity in her account for over three years. She's kept her miles alive with small transactions like the MyPoints bonus, and buying a single digital track for 110 points. (Buying magazine...

The MyPoints 750 point bonus's "sweet spot" is to keep miles from expiring. For example, my partner has about 50,000 UA miles in her account, but all her recent UA flights have been on awards booked from my account. So she hasn't had real activity in her account for over three years. She's kept her miles alive with small transactions like the MyPoints bonus, and buying a single digital track for 110 points. (Buying magazine subscriptions is another low-cost technique.)

Tom -- I think you are reading into something that isn't there. Calling something a stupid (or silly) way to earn miles is based on the activity -- signing up for MyPoints, for example, or getting a consultation for hair loss (back in the day, that earned up to 20K I think). It's not a judgement on whether those miles are cheap at all -- just so happens that my example for that category was...

Tom -- I think you are reading into something that isn't there. Calling something a stupid (or silly) way to earn miles is based on the activity -- signing up for MyPoints, for example, or getting a consultation for hair loss (back in the day, that earned up to 20K I think). It's not a judgement on whether those miles are cheap at all -- just so happens that my example for that category was actually really lucrative.

I would put credit card signup bonuses in their own category. I just didn't include them in this analysis. But yeah, they generally have a very low acquisition cost as well.

UAPhil -- I agree. I generally put unbonused spend on SPG as well, as I value them at greater than 2 cpm.

Also, I find I can almost always get greater value out of un-bonused spend with miles and points than I can with cash back. For example, SPG Amex points are worth about 2.2 cents each, so wherever Amex is accepted I use the SPG card for un-bonused spend. And I'm always chasing annual or other bonus thresholds (for example $10,000 spend on Citi HHonors Reserve for an annual free night, or needing some additional Southwest spend to renew my Companion Pass).

Travis, there are other factors that can sometimes make it worth buying miles at the same or even a higher price than you redeem them. For example, the flexibility of Southwest awards (which are fully refundable) makes it worthwhile for me to make award booking when my plans are likely to change, and revenue bookings when my plans are firm. (Yes, revenue bookings have no change fee, but the restrictions on reusing the funds make...

Travis, there are other factors that can sometimes make it worth buying miles at the same or even a higher price than you redeem them. For example, the flexibility of Southwest awards (which are fully refundable) makes it worthwhile for me to make award booking when my plans are likely to change, and revenue bookings when my plans are firm. (Yes, revenue bookings have no change fee, but the restrictions on reusing the funds make them much less flexible than award bookings.) Bottom line - if I'm short on Southwest miles, I'm willing to pay a little more for them than their redemption value to gain this flexibility.

(Along the same lines - when Southwest dropped some fares recently, I changed a points booking to save 2,000 points, but did not change a revenue booking to save $30.00, even though the value of the savings was about the same, because of the added hassle of tracking and reusing the ticketless travel funds.

According to your chart, sign up bonuses = stupid stuff

I personally just value my miles at 2c per mile. It makes the math easier when I do it in my head at the store. $200 VGC at 5x = 1000 miles = $20 which is more than the $7 fee.

Nice exercise, but much like many in the scientific world, convenient assumptions like ignoring spend to meet sign-up bonuses and ignoring category bonuses, to make a theoretical point rings hollow as I think few, unless they are meeting minimum spend to get a sign up bonus, are only spending at 1x.

Cash back at 2% is better than earning miles at 1x = not such an earth shattering discovery!

I would recommend using more realistic factors in the next exercise.

Hello, my name is Tom and I'm a domestic economy redeemer. You've heard of people like me? Well, I'm one of them. Really.

I'm more than delighted to redeem AA miles for a $450-$500 domestic roundtrip, a trip I have to take anyway. I consequently value AA miles at maybe something like 1.5 cents and, absolutely yes, I wouldn't dream of using a miles card for ordinary daily 1x spending. That's why God, or Citi...

Hello, my name is Tom and I'm a domestic economy redeemer. You've heard of people like me? Well, I'm one of them. Really.

I'm more than delighted to redeem AA miles for a $450-$500 domestic roundtrip, a trip I have to take anyway. I consequently value AA miles at maybe something like 1.5 cents and, absolutely yes, I wouldn't dream of using a miles card for ordinary daily 1x spending. That's why God, or Citi anyway, created the Double Cash card (2% cash back).

The consequence of the foregoing means that the Prestige, with its 1.6 cents per point and its 3x bonus categories, essentially combines with the Double Cash card to squeeze out mileage cards completely. In other words, for me it's the Double Cash for daily unbonused spending and the Prestige for air/hotel spending at 3x. (Citi also gives me an annual 25% points bonus.) There's no room for anything else, analytically speaking.

The other key point here is that efficient miles usage requires the finding of "saver" space while TYP usage for an AA ticket is an "any ticket/any time" redemption.

That's the simplified version of what I do.

I'll leave Amex points and short-haul Avios redemption on AA for another day since, as Travis has already noted, when you really dive into this stuff the analysis can get somewhat involved.